Arch Linux is highly respected throughout the Linux community as a cutting edge, well designed, rolling-release Linux distro with superb documentation. But at the same time, it is also discarded as a non-option by many Linux users, including experienced ones, for being time consuming to install and configure. I fall into this latter group. So, what’s a self-respecting Linux user supposed to do if (s)he wants to run Arch Linux but doesn’t want to a dedicate a whole weekend to it? Enter Manjaro, a Linux distro based on Arch. It is important to note that Manjaro is not just a re-branded Arch spin. In fact, it’s not truly an Arch system, and it does not use the Arch binary package repositories. But it’s dependent on Arch and it supposedly maintains all of the desirable features of Arch, while at the same time trying to mitigate or solve some of Arch’s less than desirable traits. We will now proceed to examine Manjaro from quite a few different angles to see if it reaches its goal. I have installed the Cinnamon spin of Manjaro version 0.8.8 on a new Lenovo Thinkpad T530 laptop, and a very old Dell B130 laptop, and have been using Manjaro as my daily driver since October of 2013. I also installed an 0.8.9 preview version of the next Manjaro Cinnamon edition on an older Acer 4810T laptop. Most of the screenshots in this review show the new look featured in the 0.8.9 version of Manjaro Cinnamon.

Installation

★★★☆ (Weight: 5%)

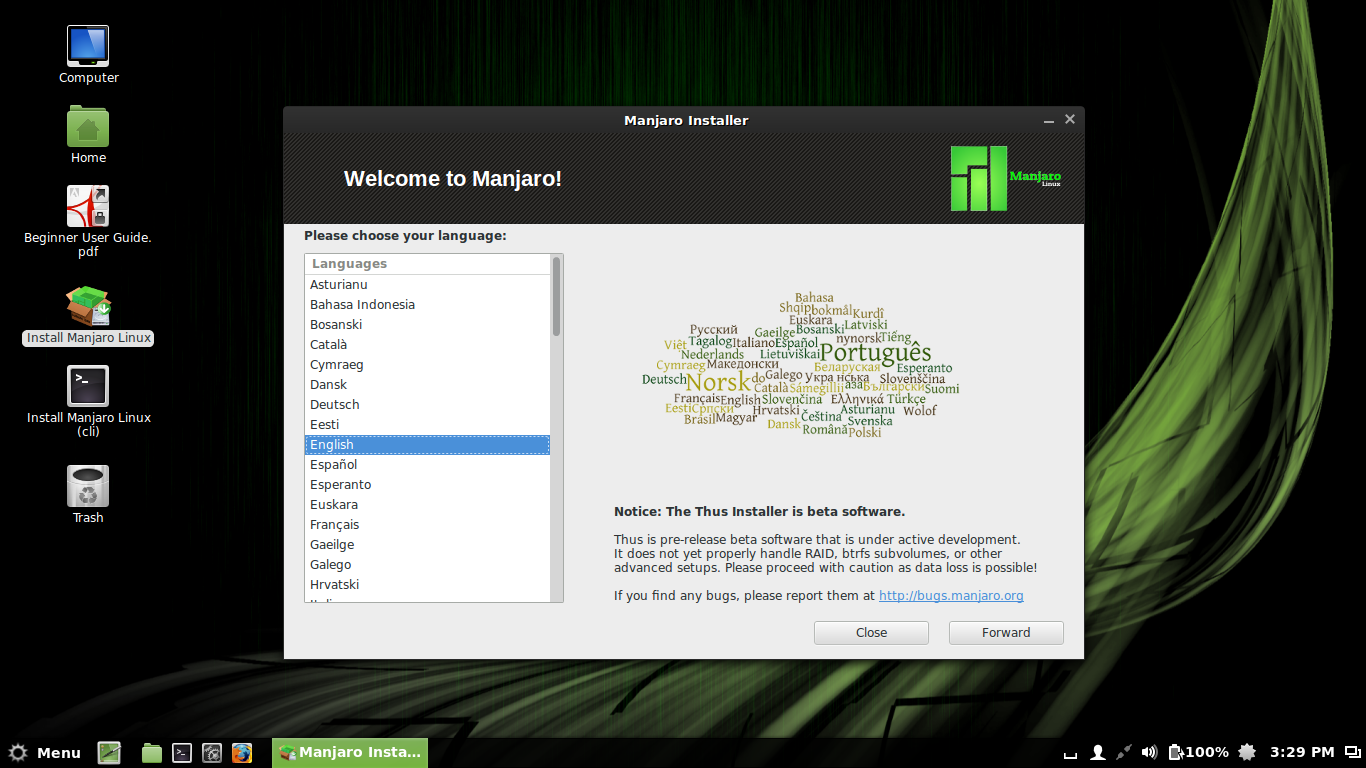

One of the most common complaints about Arch, be it founded or not, is that it requires much more technical knowledge and manual configuration to install. So logically, Manjaro tries to impress by offering an installation process that is considerably more streamlined and automated than that of Arch. All the different spins of Manjaro come as live images which, depending on their size, can be burned to a CD or DVD or else written to a USB stick. This allows the potential Manjaro user to first try out the system without risk and then later install the system if desired, using one of the two included installer programs. The CLI installer runs in a terminal window, and is still labelled as “stable” compared to the graphical installer, which is still in beta at the time of this writing. The CLI installer is plenty easy to use as far as ncurses-based installers go, and is a good fallback option that I have successfully used on some systems. But I would recommend trying the pretty new graphical installer first. It’s named Thus, and here’s what the first screen looks like:

(Click to see all the different steps of the installer)

The installer begins by offering its interface in an impressive array of languages, which feels very inviting. The next step is a locale selection. This is followed by timezone selection, aided by a nice point-n-click map. Next comes keyboard layout selection. Then comes the partitioning options step. The default option of “Erase disc and install Manjaro (automatic)” comes with a warning: “This will delete all data on your disc”, and does not seem like a very wise default choice. If this default option is desired, it offers checkboxes for optionally enabling disc encryption, LVM schemes, and a separate /home partition. The other major installation choice, which apparently does not offer the above optional perks, takes the user to a manual partitioner in “Advanced installation mode”. The partitioner is easy to use, and I have no complaints about it. It offers a wide selection of filesystem choices for formatting the partitions, including Btrfs, although I chose EXT4 on all of my systems. Changes to the partition scheme are committed by the “Install now!” button, but not before a final window appears for confirming the changes about to be made. I applaud the developers for including this final summary step. If the user again approves the changes, the installer uses a clever trick of installing the system in the background while simultaneously allowing the user to configure the username and password. This includes an optional checkbox to “Use a root password”. I’m not too clear on what this option does. I was hoping that it would allow choosing between an active root user account with a password or else an Ubuntu-style disabled root login with all administration done via sudo in the first user account. However, I left the box unchecked and yet still later found the root account to be active with the password I had set for my main non-root user. So this one needs some additional explaining. This step of the installation also allows the option to log in automatically to the user account being created, but by default it requires the password, which is a wise default. The next step shows a simple slideshow of Manjaro features while the rest of the system is copied to the target partition. The whole process took less than 10 minutes on all of my systems, despite their relatively slow spinning hard disks.

On the new T530, which is dual-booting with Windows 8, neither the graphical nor the CLI installer could manage to install a bootable system with a working GRUB boot loader that can boot between Manjaro and Windows 8. So I simply took the easy way out and disabled Safe Boot and installed Manjaro in legacy boot mode. On the extremely rare occasion that I need to boot into Windows, I can just re-enable Safe Boot in the BIOS and it will only be able to boot Windows 8. Then I re-enable legacy boot to get back into Manjaro. But users needing to frequently switch between Windows 8 and Manjaro might still need to wait for future iterations of the CLI and/or graphical installers. The developers do have Safe Boot-compatible installation as a priority for the installer, so it will probably start working sooner rather than later.

In reality, a good rolling-release distro like Manjaro should not require another re-install, so the installation program will soon be forgotten by the user and will possibly never again be re-visited. But all the efforts to make Manjaro easily installable are very much appreciated, and greatly lower the entry bar to get into a system with all of the purported benefits of Arch Linux. So let’s give Manjaro 3 out of 4 stars in this category.

Aesthetics

★★☆☆ (Weight: 5%)

The default appearance of a given Linux distro is by no means the most important grading criteria, which is why this category’s grade only weighs into the final rating at 5%. Nevertheless, first impressions are extremely important, and can sometimes be the factor that motivates an inexperienced user to keep or abandon the entire distro after a superficial period of brief testing. So how does Manjaro present itself to potential users? Basically, I would say that it’s nothing to write home about, and the overall appearance is neither strikingly beautiful nor noticeably ugly. Here’s what users will see at first boot:

I don’t like black elements in the interface, so I quickly changed the window border theme and the Cinnamon desktop theme to something lighter. Likewise, I don’t particularly like the GTK3 theme, which eschews up/down arrows on the scrollbars in favor of a more modern but less practical look. But these tendencies seem to be pretty much the norm in most Linux distros these days, and I am considerably more traditionalist than most users. So I don’t fault Manjaro too much for its choice of themes. The wallpaper is similarly inoffensive albeit drab, and there’s only one other available wallpaper included to choose from. But with some configuration, I made it look much more pleasant to my eyes:

Something else worth noting is the lack of Plymouth or any other bootsplash system by default. Arch Linux and Manjaro users alike will probably hate me for saying this, but I do like a nice smooth splash screen during the boot process, and Manjaro is in the minority of distros that don’t include one by default. I miss the option that used to be present in some of the older versions of the Manjaro graphical installer, which offered a checkbox to enable Plymouth on the installed system.

Font rendering is probably the most important and difficult to change aspect of a Linux distro’s aesthetics. As a heavy computer user, I expect the fonts that I stare at day in and day out to be nothing short of superb. Ubuntu has always been the standard for beautiful fonts with perfect subpixel hinting for LCD screens by default, straight out of the gate. Some other popular Linux distros still have awful font rendering, especially in terms of subpixel hinting, and achieving the same font quality as Ubuntu is a protracted and unintuitive process. Fortunately, this is not the case with Manjaro. While I don’t like the default choice of Sans fonts, simply switching all the fonts to the DejaVu Sans font family gives very pleasing results on my LCD screens, with good subpixel hinting. It doesn’t appear to be quite the same stellar font rendering configuration that Ubuntu uses, but it is still very good to my eyes.

So, Manjaro is not to be chosen just for its looks, nor should it be avoided by the same token. Let’s give it 2 out of 4 stars for this category.

Refinement and Default Configuration

★★★☆ (Weight: 15%)

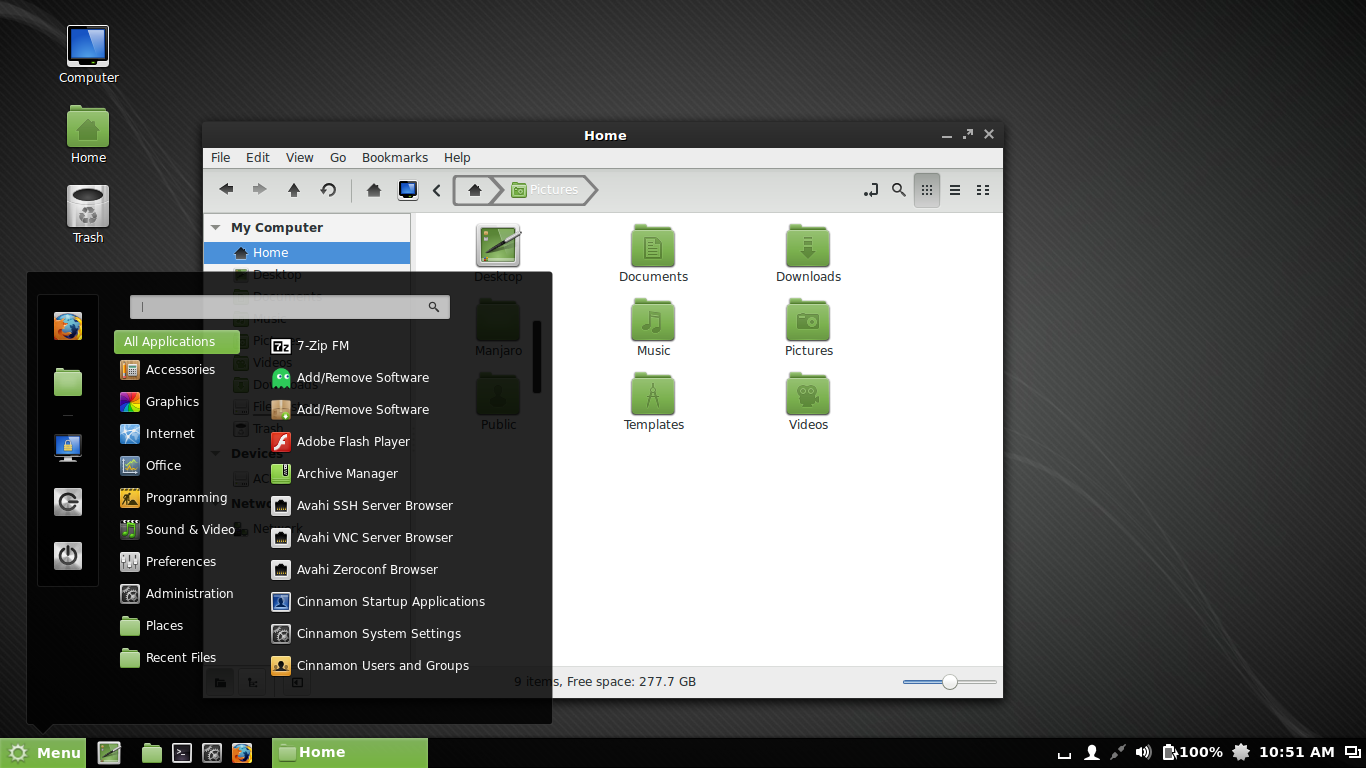

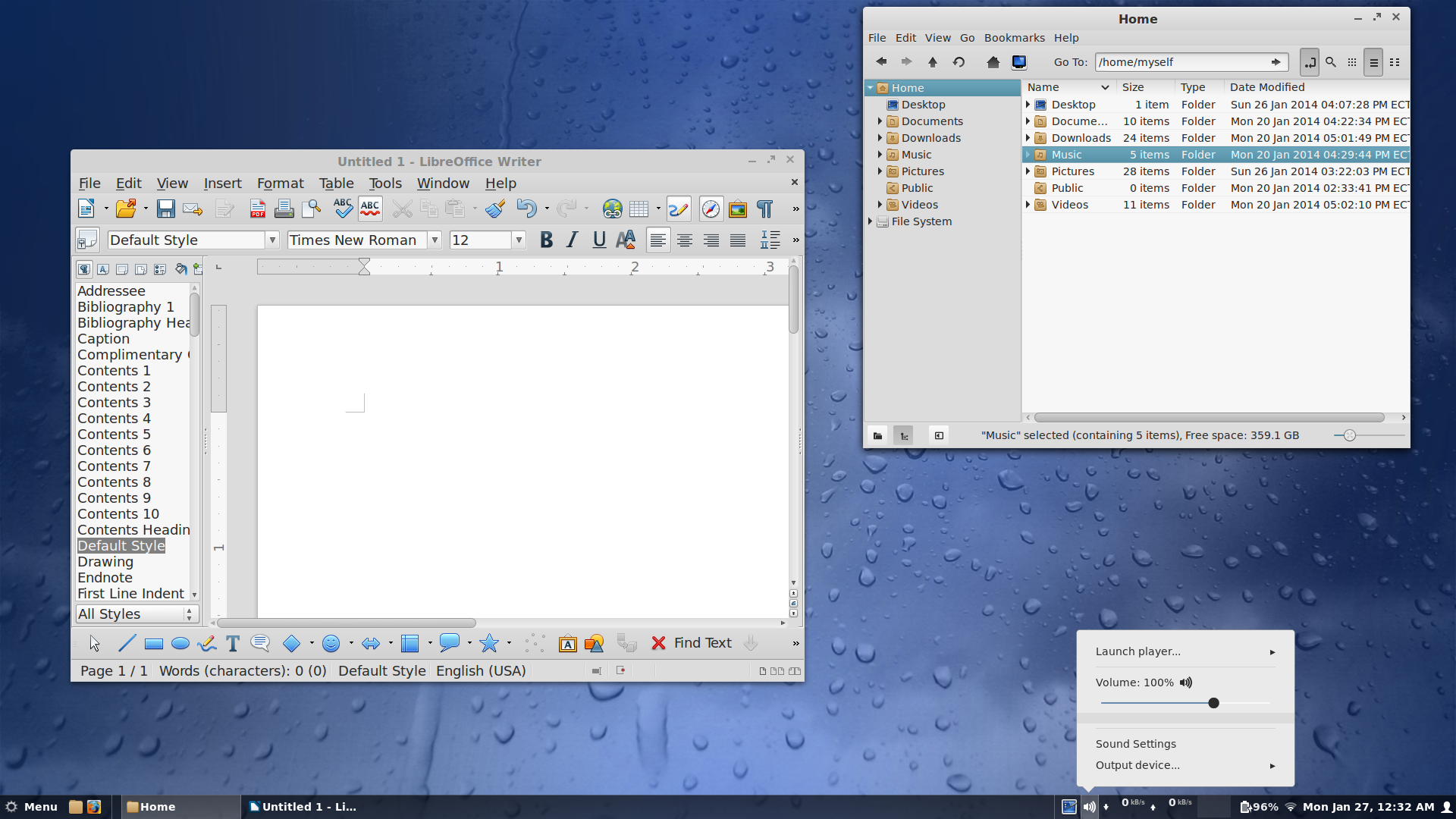

After using a computer for many hours on end, day after day, week after week, the little details can either make or break the experience. Manjaro does pretty well in this sense, at least in the version that I chose. The Cinnamon desktop environment is smooth, traditional, and generally stays out of my way. It allows popup notifications to be turned on or off, and the notifications tray applet can be removed. I personally find unread notifications that stack up in a queue hidden in an applet in the system tray to be extremely distracting and useless, so I always remove the notifications applet from Cinnamon, and the resulting notifications behavior is just the way I like it. Cinnamon offers a very nice coverflow Alt+Tab animation that shows the different windows in a useful 3D arc. The default Cinnamon menu is simple and clean and features a good search mechanism for programs and recent documents. It also has an applet in its applet repository that allows individual programs’ output volume to be controlled via the Pulse sound system with a tray volume control applet, which also doubles for music player controls. The Nemo file manager has basic right-click conveniences such as opening a terminal to a directory, opening directories as root, and compressing/uncompressing items. However, I do miss an option to open files for editing as root. Nemo also has nice right-click options for copying or moving files and directories to another location. Thumbnail previews work well out of the box for both picture and movie files. One major annoyance is that some directories do not allow re-sizing of the columns, resulting in truncated filenames. This seems to mainly be the case for directories on top of GVFS and files in the Trash bin. Speaking of GVFS, it wasn’t installed out of the box, so no Samba browsing was possible until I installed the gvfs-smb package. Likewise, I had to install and configure the nss-mdns package and enable the avahi-daemon in order to connect to my wireless printer that is shared over the network. There was also no PDF viewer installed by default. Apart from this omission, the default program selection is fairly limited, which I don’t necessarily consider to be a defect. I do like the fact that VLC and Flash and Java are included out of the box, as well as the Firefox browser for immediately getting online and using multimedia, even when using the live system. Likewise, practically every Linux user will need an office suite, and Manjaro offers the real McCoy— LibreOffice Writer and Calc are installed by default. These seem to be the most important programs that almost every user will need, and any other needs can be easily installed via the package manager, discussed later.

Well done here, Manjaro. Although exhibiting a few papercuts here and there, the overall system with Cinnamon on top is refined and productive out of the box. It gets 3 out of 4 stars for this important criterion.

Stability

★★★★ (Weight: 20%)

Manjaro is remarkably stable, which is especially noteworthy given its rolling-release nature. During general usage, I have not experienced any Xorg server crashes or kernel panics, and indeed most of the user applications have been very well behaved during the past months of using Manjaro. Additionally, stability continues to be excellent even after several dozens of suspend/resume cycles. But stability isn’t always so easy to maintain after upgrading packages to newer versions. Fortunately, Manjaro’s three stage Unstable/Testing/Stable package testing process offers additional protection from bugs that might creep into the Arch packages that Manjaro it is based on, and the additional effort appears to be paying off. In addition to avoiding bugs in programs, it also reduces the likelihood of an update resulting in package dependency issues. This is a huge advantage for Manjaro in an extremely important criterion, and it gets a full 4 out of 4 stars on this one.

Performance and Resource Usage

★★★☆ (Weight: 20%)

Manjaro is reasonably efficient and well performing. Tribute to this fact is paid by my 8 year old Dell B130 laptop with a slow Celeron M processor, a slow spinning hard disk and 1 GB of slow RAM. First of all, I disabled unessential Cinnamon session startup items such as the Pamac system updater applet, Caribou, and the Manjaro Settings Manager. Now, despite the age and limitations of this old laptop, 32-bit Manjaro boots to the MDM login window in about 25 seconds, and it runs the Cinnamon desktop environment smoothly, using less than 170 MB of RAM with no swap. Firefox cold launches in about 6 seconds the first time and 3 seconds after that. Surprisingly, Youtube Flash videos play back smoothly at 480P fullscreen. LibreOffice Writer cold launches in less than 9 seconds and only about 2 seconds on subsequent launches, still without touching the swap space. The Nemo file manager launches in about one and a half seconds. Shutdown also is quick for an old system, at well under 10 seconds.

On my less old Acer 4810T, the 64-bit version of Manjaro takes a bit longer to boot, at around 26 seconds, which is still pretty good. RAM usage is also acceptable, at about 280 MB of RAM when logged into a basic Cinnamon session with unessential startup items disabled. Finally on the T530, the 64-bit version of Manjaro only takes about 18 seconds to boot to the login window, and shutdown usually takes less than 5 seconds.

On all of my systems, CPU usage is generally quiet, and fan speed is minimal on the two newer systems. The default installed system uses around 3.7 G of disk space on a 64-bit system. So Manjaro seems to be a good choice for both new and old systems.

The only noticeable slowness appeared when I configured a Plymouth bootsplash screen. For some reason, enabling Plymouth drastically increases boot time on all three of my laptops. For example, on the old, slow Dell, boot time increased from 25 seconds to 40 seconds with Plymouth. While this might appear to be simply a side effect of adding Plymouth to a very slow, old system, it is noteworthy that Ubuntu 13.04 with its default Plymouth bootsplash booted in a cool 28 seconds on this very same ancient machine. So something about Plymouth doesn’t get along with Manjaro’s init system, and I would really like to see some kind of fix for this.

Overall, Manjaro seems to be a good choice for both new and old systems, and it deserves a very respectable 3 out of 4 star rating for performance and resource usage.

Ease of Use, Configuration Utilities, and Hardware Auto-detection

★★☆☆ (Weight: 10%)

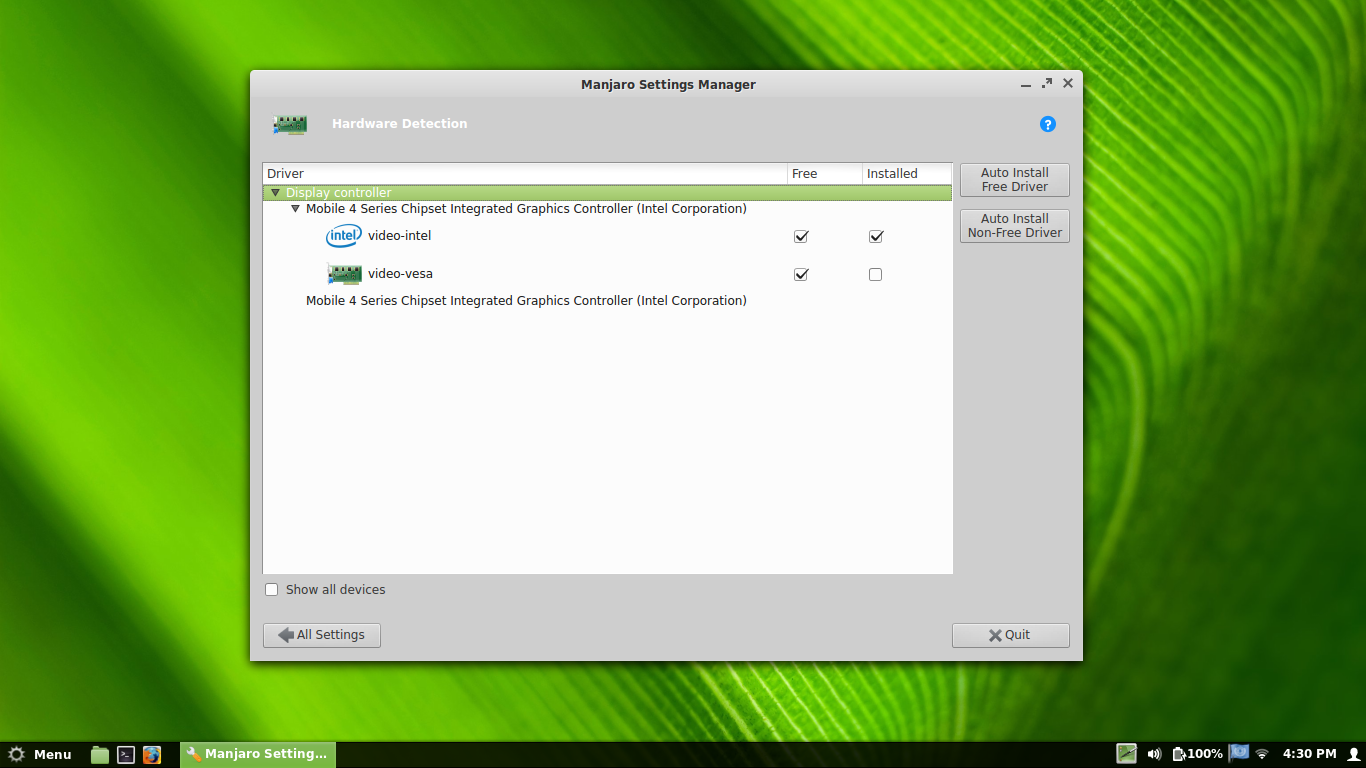

After the installation process, this criterion is probably the most interesting for users wanting to use Arch but tending toward Manjaro because of its purported ease of use. Overall, I think Manjaro is making admirable progress toward its goal, but still has some work to do. In terms of hardware support, practically any Linux distro can support more or less the same hardware components by virtue of the kernel and its drivers that can be made to work with any distribution. Likewise, all of the essential GNU utilities and services can also be configured to work with any GNU/Linux system. However, the amount of time and research that it takes to do so varies greatly depending on the utilities provides by the Linux distro. Arch Linux strongly promotes a manual approach toward system configuration, insisting on research and learning the technical underpinnings of the system and manually tailoring everything to perform the exact tasks and support the exact hardware that are required. I personally do not want to spend that much time and effort to get a working system, and even less so if I am helping somebody else to install and configure their system. So I applaud Manjaro’s pragmatic approach toward easy and automatic configuration of the base system. The live system booted and automatically configured all the hardware on my three laptops. This includes the old, proprietary Broadcom WiFI driver for my old Dell B130, which was hardly ever supported out of the box on Linux distros of yesteryear. Similarly, my other two laptops with Intel wireless also connected to the network immediately without anything more than my wireless network passphrase. All of my laptops use Intel graphics, which usually works flawlessly on pretty much any Linux distro. However, users on other distros with Nvidia or AMD graphics usually have to suffer through a considerably more complex process to install proprietary drivers, and their hassles usually re-appear on every kernel upgrade. I have never tried it, but most Manjaro users with more complex proprietary driver needs seem to be happy with Manjaro’s MHWD hardware configuration tool, which features a nice new GUI as of Manjaro 0.8.8:

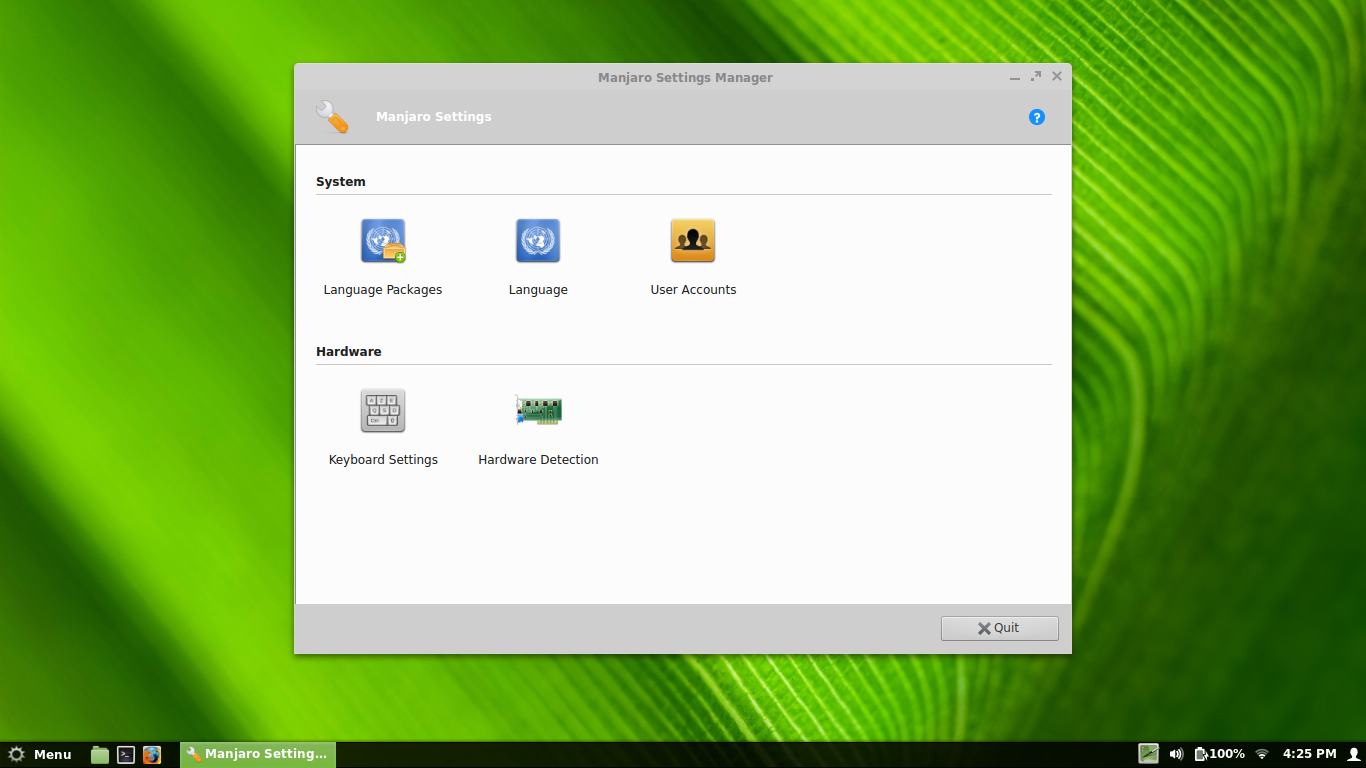

Manjaro also worked well with the special function keys for multimedia controls and suspending the system on all of my laptops. The touchpads all worked well, and a simple option in the Cinnamon settings allows two finger scrolling with the touchpad. Manjaro also has a few other custom created GUI system configuration tools in the Manjaro Settings Manager:

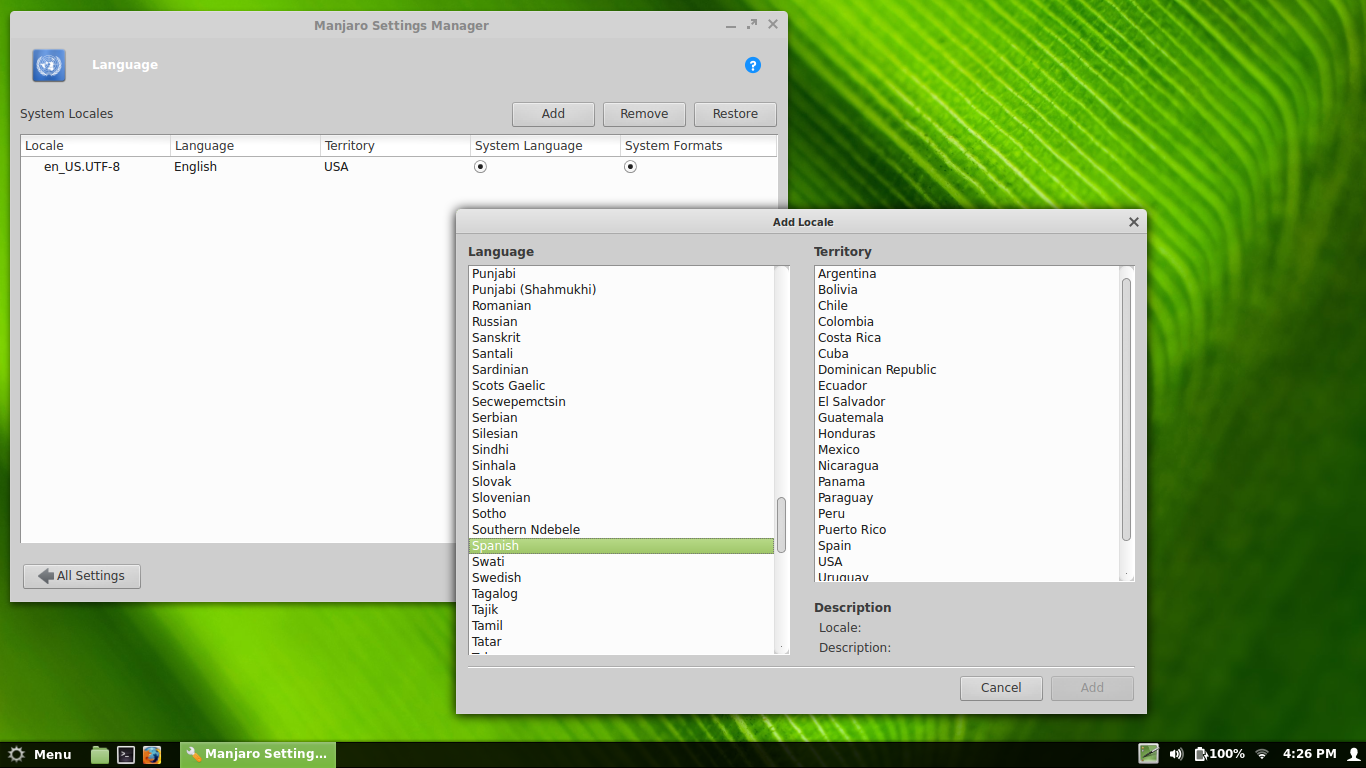

One of the important tools that I greatly appreciate is the “Language” tool for selecting additional languages that will be used on the system:

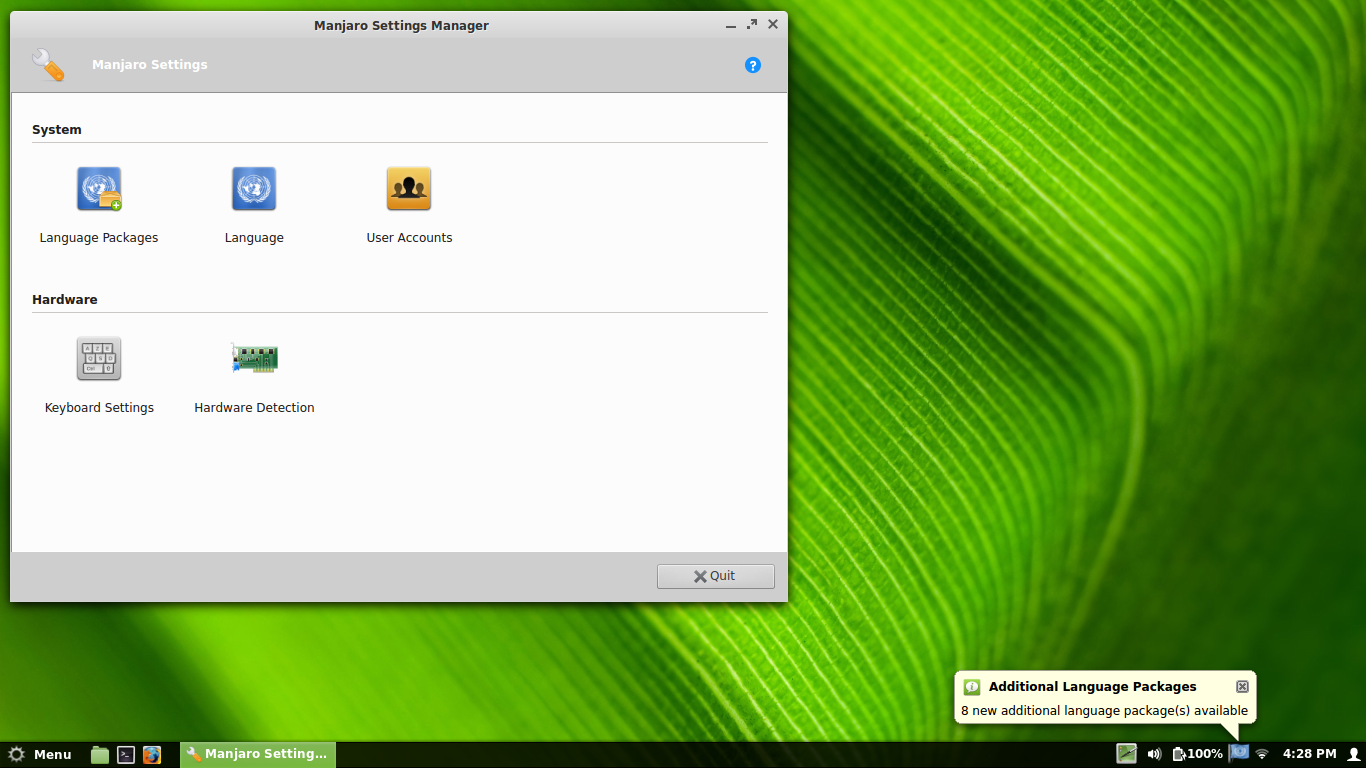

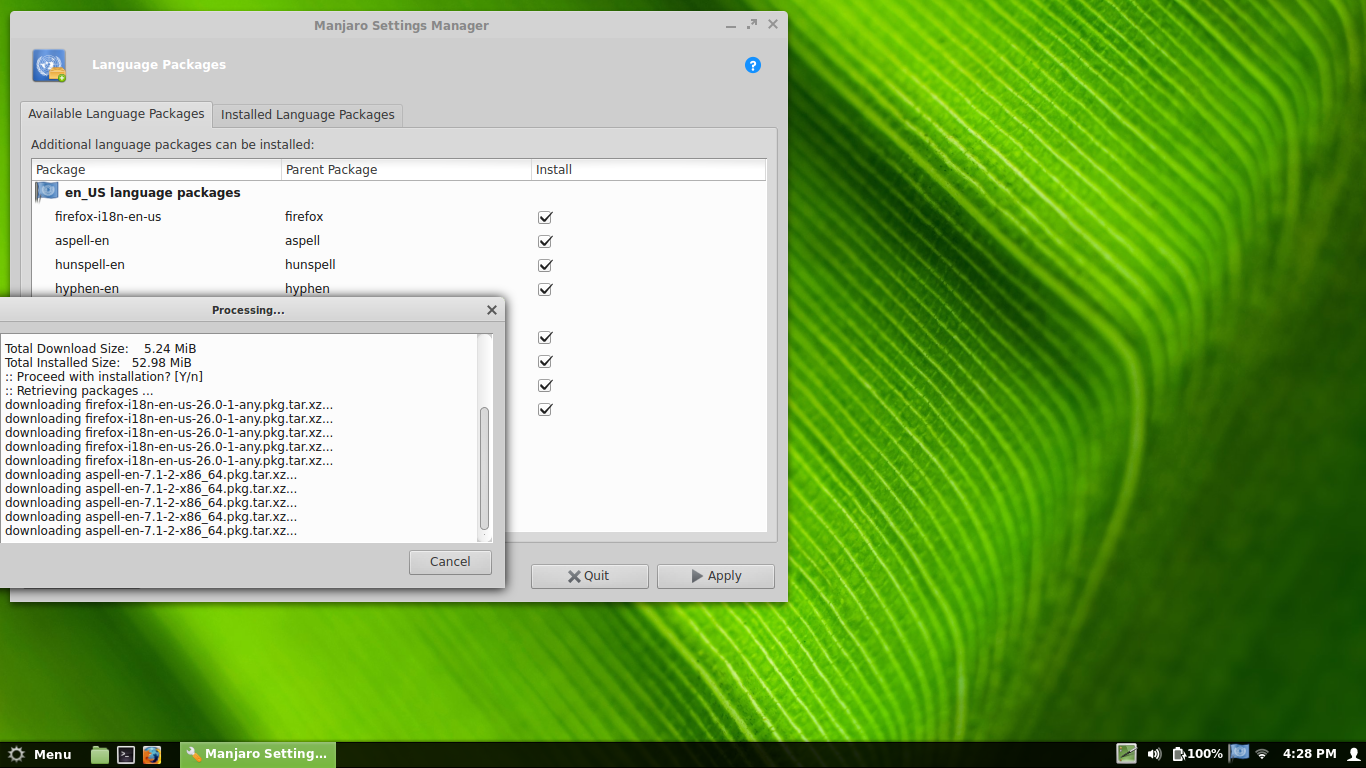

This is a huge boon for users that type in more than one language, or for systems that are used by different users that don’t speak the same language. Simply selecting additional locales with the “Language” tool will make the system prompt you to install the language packs for those new locales, thus enabling spellcheck support for the different languages on different spellchecker systems that various programs use:

This even makes it easy to select a language from the login screen and login to a fully translated desktop environment with all of the programs localized in the user’s native language. My only suggestion for the locale tools would be to combine them into just one tool with tabs, one tab for selecting the desired locales and another one for installing the language-related packages for those locales. As it is, the “Language Packages” tool comes before the “Language” tool in the Manjaro Settings Manager, which suggests that one should be used before the other. However, in reality, the “Language” tool needs to be used first to select locales before the “Language Packages” tool will be able to actually install the related language packages. But at any rate, it’s great to see that non-English languages are welcomed and supported on Manjaro, making it much more appealing to potential users around the world.

There is also a simple tool for adding and administering Linux user accounts, which is not needed on advanced desktop environments like Cinnamon that already include their own user management tools, but it is very nice to have on lightweight Manjaro systems running something like Openbox or LXDE that don’t offer their own user management GUI.

Manjaro has made great progress on GUI configuration tools and general ease of use, and is remarkably easier than Arch in this sense. However, I think it still has a ways to go before it can compare to the depth of functionality offered by a few exceptionally powerful administration tools such as YaST on openSUSE or MCC on Mageia. Those tools offer desktop-agnostic GUI tools for configuring everything from the GRUB bootloader, system service startup, wired and wireless network, Windows domain authentication, NSS mounts, firewall, security frameworks, hostname, printers, and a whole lot more. YaST even works in console ncurses mode, so the system can be easily configured and repaired from the console in the case of a broken Xorg server. So we’ll give Manjaro 2 out of 4 stars for this category, and let’s hope that it keeps making good progress toward developing easy system administration tools.

Package Management, Package Selection, and Update Lifecycle

★★★★ (Weight: 20%)

A good package manager is an essential feature of a successful Linux distro. This goes hand in hand with good testing of package updates. Although a Linux system might work well after the initial install, as time goes on and updates are installed and new software is added or removed it can turn into a cluttered mess of broken packages and failed dependencies. This often occurs when the user wants new or updated versions of some pieces of software and adds many different package repositories from different sources, some of which might contain conflicting versions of packages or later become unavailable. Or, updating from one major version of a Linux distro to the next sometimes results in a broken system that is best fixed by just reinstalling from scratch. Fortunately, Arch Linux goes a long way toward remedying this problem, and Manjaro improves upon it even further.

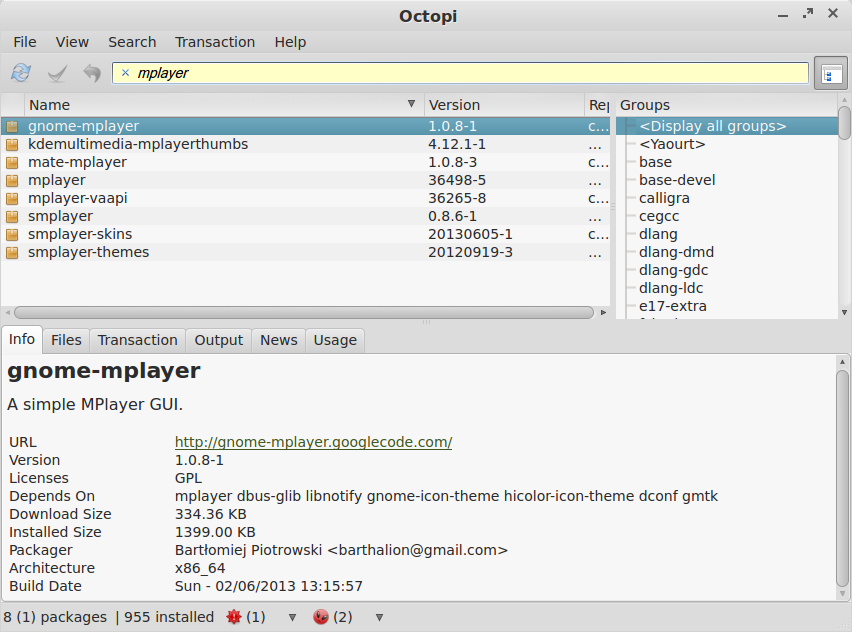

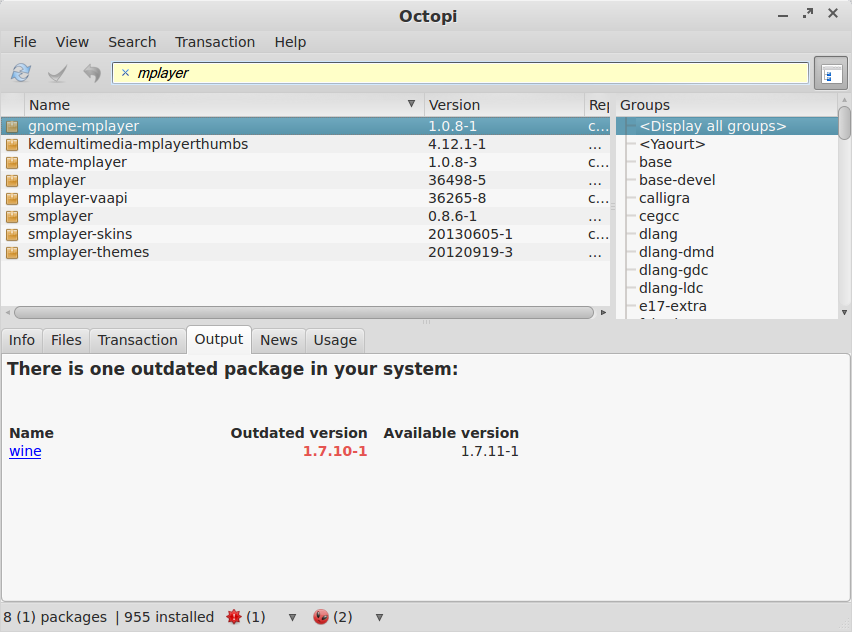

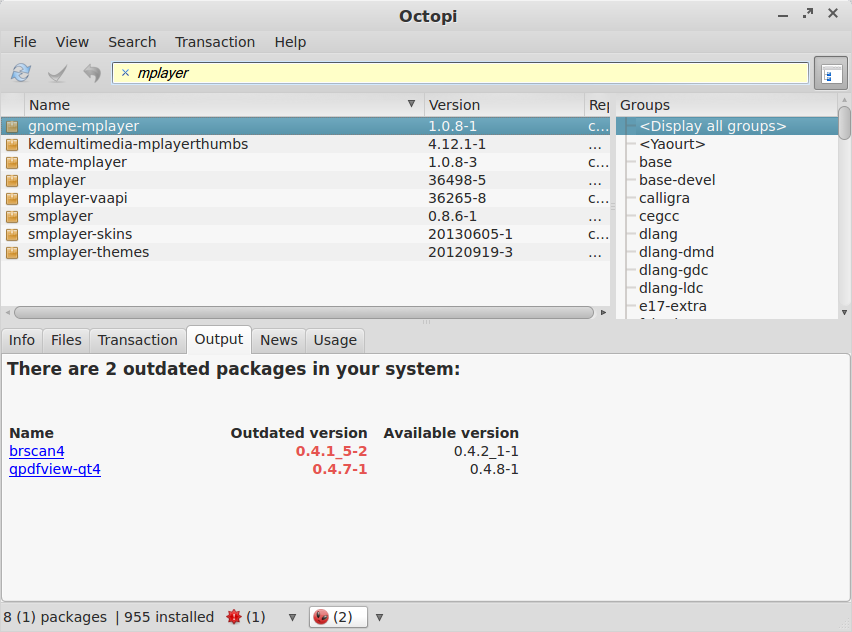

A core tool of Manjaro is pacman from Arch Linux. It is a smart and fast package manager with a plethora of options that I won’t discuss here. As far as command line package managers go, it’s relatively easy to use, although its commands are somewhat more cryptic than something like yum or even apt-get. I personally find pacman to be fast and easy for just installing a quick package here and there if I already know the name. I also find it useful and easy for updating the system. But I don’t like using it for browsing available packages or searching for them. Manjaro developers recognize that a simple GUI packager is an important requirement for many desktop Linux users, and they actually offer two options: Pamac and Octopi. Of the two, I strongly prefer Octopi. Unlike Pamac, Octopi does not automatically refresh the package database every time it is launched. I refresh my package databases regularly and I stay informed on Manjaro updates, so I don’t need my package manager to go through the time consuming process of checking for updates every time I open it. I like the way that Octopi clearly presents the number of outdated packages along the bottom:

Clicking on the outdated packages warning brings up a list of packages for which updates are available:

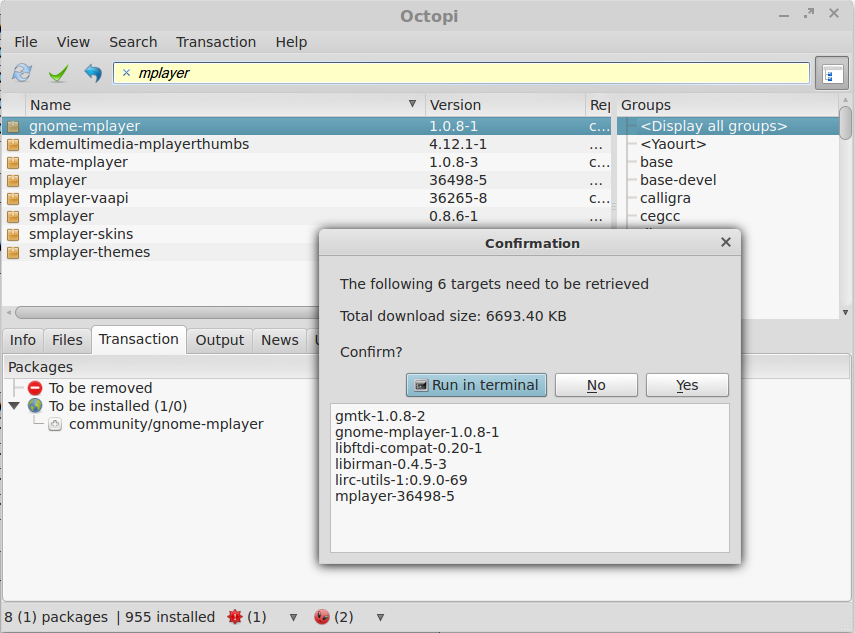

Normally when a new Manjaro update pack is released, there will be hundreds of packages in this list to be updated. These packages can be updated all at once with Octopi to keep the system up to date. Octopi also does a good job of informing the user of dependencies that will be installed along with selected new packages to be installed:

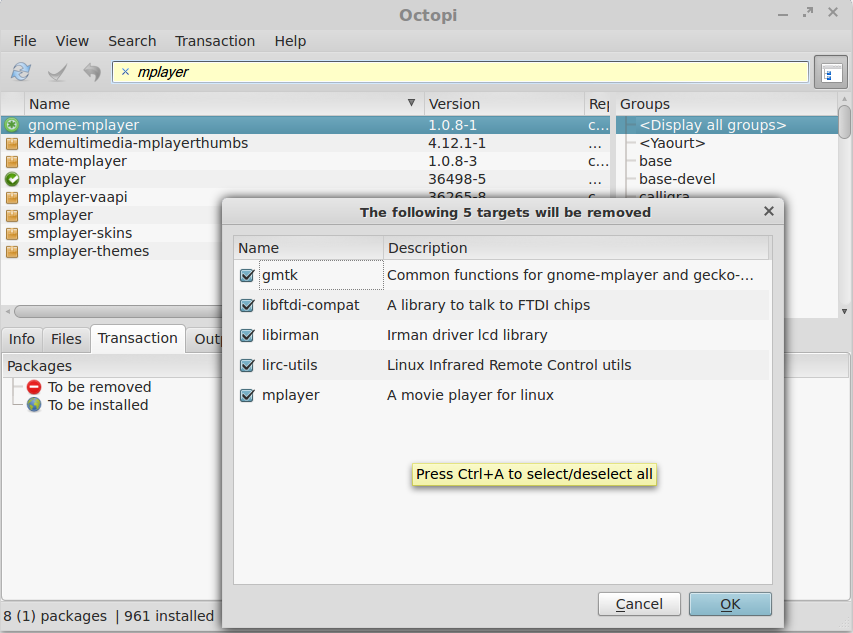

More important still, Octopi also un-installs unneeded dependencies when removing the parent package that previously required them:

Octopi also does a very nice job of interfacing with one of the most enviable features of Arch Linux: the Arch User Repository. The AUR is a truly unique collection of recipes for automatically downloading, optionally compiling, packaging, and installing an astonishingly wide variety of practically any software that is not officially available in the Arch (or in this case, Manjaro) repositories. It’s probably the single most important feature that attracts new users to the Arch ecosystem. In my case, while using other distros I would frequently be searching Google for some obscure new software package for Linux, and I consistently ran across results in the AUR. So the AUR is a tremendously strong selling point for Arch Linux, and Manjaro was wise to include support for it in their package managers. Octopi clearly shows a button that reports the number of outdated packages from the AUR, and they can be easily updated individually or in a batch:

Arch Linux is probably the most famous and well executed rolling-release style Linux distribution. A rolling-release system is designed to be constantly updated, usually implying a constant stream of small daily updates to different installed packages. This contrasts sharply with the interval-release system of most popular Linux distributions such as Ubuntu and Mint, Fedora, openSUSE, and many others. These aforementioned distributions have relatively long development periods, usually lasting months, which eventually culminate in a “stable” released product. From then on, during the entire support lifecycle of that release the developers usually only release bug fix and security updates to the software packages in their stable package repositories. Updates to programs that include new features are usually not made available so as to avoid introducing instability into the released product. This means that users often can not install the latest versions of new packages that offer essential new features or changes that they have been waiting for, and therefore users must wait for a relatively long time, sometimes 6 months or more, until the next stable version of the distribution is ready to offer the updated software in question. As a partial solution to this problem, some interval-release distros offer additional repositories that provide updates for some specific software titles as they become available during the supported lifecycle of the distribution release. These additional repositories can be optionally added, and they take precedence over the main stable repositories and cause the package manager to install newer versions of a specific software title. I personally do not favor this approach for several reasons. First of all, add-on repositories are often only available for popular software titles, whereas more obscure pieces of software are often not worth the trouble of creating a dedicated update repository. Second, these add-on repositories sometimes conflict with the package versions in the stable repository or with other add-on repositories. Third, the add-on software repositories occasionally stop working, which results in failed system updates or broken package dependencies. Additionally, the add-on repositories are usually not part of the primary infrastructure of the distribution project, and are often hosted on just one or two different servers with no other mirror servers. This can result in occasionally overloaded servers and poor package download speeds. Finally, I find it to be a rather long and protracted process to search around for packages, first in the main stable repos, then in the add-on repositories, then to add new package sources to the system, refresh the package database, and finally install the desired piece of software. Arch Linux with its rolling-release distribution design offers a refreshing change from the aforementioned system. Unlike an interval-release system, Arch receives a constant stream of updates, and new versions of most software titles appear almost immediately in the Arch repositories whenever the developer releases it. This means that at any given moment the user can update the entire Arch system to all the latest stable package versions and effectively be running the latest release of Arch. So in theory, an Arch system can be installed just once and then roll along with frequent system upgrades without ever being re-installed again. While it is true that there are other rolling-release distributions such as Debian Unstable and Testing, they usually do not exhibit the same degree of excellence as the system that Arch has designed. For example, Debian Unstable, as its name suggests, is not intended to offer a stable system to its users. Instead, the Unstable branch is the first step in testing and debugging the next future stable Debian release. Although many users have had varying degrees of success at running a stable system on Debian Unstable, there is something to be said for Arch’s model, which is designed to offer a constant stream of stable updates to its users after rigorous testing. Additionally, Debian Unstable and Testing do not truly roll. They receive a constant stream of updates for a long period of time, but as the development process nears the next stable Debian release, first the Testing branch followed by the Unstable branch eventually end up freezing for a period of time as developers concentrate on stabilizing and preparing the final stable release. During this time period, users are sometimes stuck without security and feature updates. Arch, on the other hand, never has fixed stable releases. Rather, the development process is focussed on keeping the entire set of packages always up to date and yet stable at any given point in time. The Arch installer images are simply periodic snapshots of the stable branch, meant to be immediately synced and updated to the latest packages as soon as it is installed.

In the case of Manjaro, its binary package repositories are essentially snapshots of the Arch package repositories at a specific moment in time, hosted on Manjaro’s own servers and mirrors throughout the world. The initial snapshot coming directly from Arch’s stable repository is designated as “Unstable” in Manjaro. From there, the Manjaro developers and testers install these “Unstable” snapshots, and if there are no major issues the entire snapshot graduates from “Unstable” to the “Testing” repository. At this stage, a larger audience of Manjaro users try out the update pack and report any additional bugs that weren’t caught in the previous stage. From there, the update pack is moved to the “Stable” Manjaro repository, where the majority of the users will receive a thoroughly vetted update that is less likely to break their stable system. This conservative approach adds several levels of testing to the already fairly stable Arch releases, and in my experience since October of 2013 has resulted in regular updates of all my installed packages, usually every few weeks, with no major bugs that leave me with an un-bootable system or non-functional desktop. I think this extra level of stability is a very real advantage of Manjaro over Arch. And compared to an interval-release distribution, I find the process of searching and installing packages to be very simple. Instead of searching in many different places for software titles, I simply open Octopi and search for the desired package name or keyword. If it doesn’t exist in the official stable binary package repository, while still in Octopi I select the AUR for searching and invariably find a build script there that automatically downloads and installs the software. So far, I have not had the need of searching for and adding additional software repositories to the Pacman package sources list. With the help of AUR, The availability of current software is truly astonishing, including proprietary software such as closed-source Linux drivers for my printer that are downloaded directly from the manufacturer and then locally packaged and installed for my own system, commercial office suites for Linux, Skype, Google Talk plugin, obscure open source programs developed for Ubuntu on Launchpad, and much, much more.

Arch Linux users usually receive every new version of the Linux kernel as it becomes available in the Arch stable repositories. The problem is that Linux kernel releases frequently exhibit bugs and even regressions (functions that stop working) on different pieces of hardware. Sometimes a certain piece of hardware is known to be incompatible or buggy with a specific version of the Linux kernel. So it is not always advantageous to run the latest available version of this extremely important component of the system. Thanks to the previously mentioned MHWD tool, Manjaro offers a nice solution to this issue. MHWD can be used to install different versions of the Linux kernel that Manjaro maintains. In the list of available kernels is the newest cutting edge kernel release, another slightly older but still maintained kernel, and several older Long Term Service (LTS) kernels. A Manjaro user can concurrently install one or more of these different kernel versions and in this way work around most hardware issues and kernel regressions. This is another huge advantage that Manjaro offers over Arch, and I thank them for their efforts.

My only wish for improvement in this category of package management is a “Software Center” or “App Store” type of application. I personally find Octopi to meet my needs. But it must be admitted that inexperienced Linux users generally want something more like a smartphone app store to browse and install/remove packages. New users often feel overwhelmed by the sheer quantity of available packages in a long list, and they usually are interested only in the ones that have a graphical user interface. Additionally, even experienced users sometimes find it useful to be able to search for and install programs one after another without waiting for the first batch of package commands to finish first, which is a feature offered by several friendly software centers offered in popular Linux distros. I think it would be good to investigate the possibility of getting Gnome Software to work with Arch/Manjaro, so that newer users can take advantage of this attractive and friendly tool.

Despite the lack of a friendly software center, I still can’t give Manjaro anything less than 4 out of 4 stars on this extremely important criterion. The combination of a huge variety of open and closed source software offered in one cohesive and constantly updated repository system, combined with the added stability and protection of the Manjaro release process results in an extremely attractive option that leaves me with a lot more time to use and enjoy my computer and its software instead of searching for packages. This is without doubt the most compelling reason to consider Manjaro for use as a primary desktop computing system in the home or the office.

Infrastructure, Documentation, Support, and Sustainability

★★☆☆ (Weight: 5%)

Although a given Linux distribution might have an excellent degree of design and refinement, if the overall methodology and infrastructure used to develop and support it are lacking, its overall viability as a solution for production usage is reduced. An extremely small startup distro often has problems finding reliable hosting for its site and worse still for the large ISO file downloads that its users want. Sometimes the package servers of some distros are overloaded and slow, or geographically located in such a way that connections from certain parts of the world lead to high latency. Another important part of any operating system is documentation and support for its users. And finally, the project must have a way of sustaining itself in such way that all development doesn’t cease if something happens to one of its main developers. In 2013 and 2014, users of several relatively popular Linux distros received a nasty surprise when their preferred project suddenly closed its doors and ended development without prior notice. So it is important to examine these factors before committing to any particular Linux distribution.

Manjaro’s overall infrastructure is quite good. It offers its installation ISO images for direct download via Sourceforge, which is reliable and has quite a few relatively fast mirrors around the world. Most users, including myself, prefer direct downloads, but they do offer torrent files for the final releases of the official Manjaro editions. As for the Manjaro package repositories, there are quite a few of them, and they are generally fast and reliable. The useful pacman-mirrors -g command automatically updates the list of available mirrors and even automatically ranks them by speed for you. So if one mirror is temporarily down or out of sync, Pacman automatically tries the next mirror on the list. I also really appreciate the fact that Manjaro supports many different desktop environments and offers different spins that feature them. The primary development of Manjaro is actually focussed on the XFCE, Openbox, and KDE environments. However, Manjaro also prominently features the well done community editions, such as the Cinnamon edition that I based this review on. Apart from Cinnamon, other community editions of Manjaro are available for the Gnome, E17, LXDE, and MATE environments. Although some of these editions do not release installer images as frequently as the main XFCE, Openbox, and KDE editions, they can still be installed and then updated with a simple pacman -Suy command to the latest version of all the packages. All of these different editions are very much welcomed by users that want choice and variety from their preferred distributor, and are indicative of a very active and vibrant Manjaro community.

Manjaro’s website is attractive and well designed. There is a blog that keeps users abreast of the latest Manjaro development and update packs. The Manjaro forums are generally fairly friendly and welcoming to new users with a lower than average amount of elitism from experienced users. Even the developers are active on the forum and frequently respond to users’ questions, and they are friendly and down to earth. The website also has prominent links to other non-English Manjaro forums, which is inviting and nice to see. For reference, Manjaro has a well designed and clearly written Wiki too with information about getting started with Manjaro, customization and configuration of Manjaro, and troubleshooting. But the best resource for Manjaro help and configuration comes by virtue of its compatibility with Arch. The ArchWiki is a shining example of documentation for a Linux distribution. It explains in great detail all aspects of the system from its core underpinnings to end-user configuration details. Here you can find clear instructions on anything from usage of systemd to changing the text background of icons on the XFCE desktop. For many years I have referred to the ArchWiki for its clear and understandable instructions, even before using an Arch based system. This is a huge advantage of Manjaro being based on Arch that should not be overlooked, giving it a clear advantage over almost all other Linux distributions out there.

Finally, we need to look at the long-term sustainability of Manjaro Linux. This is really more of a prediction than an evaluation, given that anything could happen in the future with the project or its developers. It appears that Manjaro is prospering and popular for the time being. However, there aren’t a huge number of developers, and I hope that their development process is not overly dependant on any one person. They do have several sponsors that provide servers and mirrors, but at the time of this writing there don’t appear to be any major monetary sponsors. The Manjaro project does accept donations, which are undoubtedly very much appreciated.

So, Manjaro has a pretty good infrastructure and excellent support and documentation, but it’s too early to say with certainty what the future will hold for it. Given this uncertainty, let’s give it 2 out of 4 stars for this category.

Final Rating: 3.2 out of 4 stars

Reference: Grading Description

So there we have it. Manjaro is doing a lot things right. It gets high marks in all of the most important heavily weighted categories, and doesn’t do any worse than 2 out of 4 stars in any category, resulting in a very solid overall grade of 3.2 out of 4 stars. I have installed Manjaro on all of my systems, and I would highly recommend it to any intermediate to advanced Linux user. Returning to the question mentioned in the first paragraph, does Manjaro reach its goal of maintaining all of the desirable features of Arch, while at the same time mitigating or solving some of Arch’s less than desirable traits? Absolutely. Many thanks to Arch for the superb base that they provide, and hats off to the Manjaro project for offering us this compelling and innovative distribution.